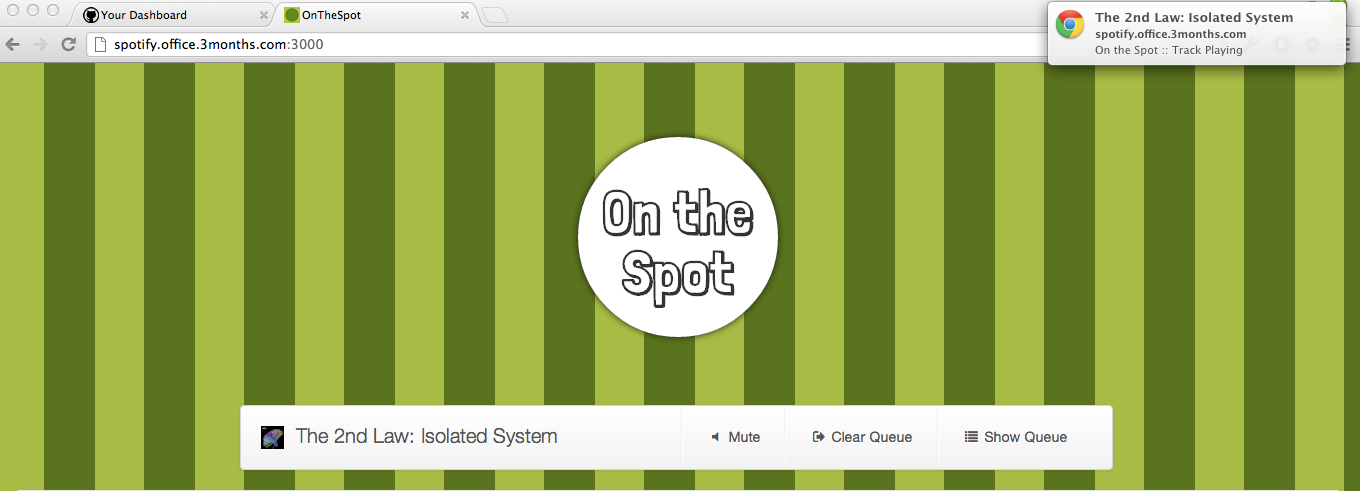

HTML5 Notifications

On the Spot is a pet project that I tend to develop with bleeding-edge features in mind - something a bit more volatile than Latter, which is used heavily enough to justify a more cautious development process. In this post, I’m going to detail how I added HTML5 notifications to On the Spot, the upsides and downsides, and the Coffeescript class that does it all.

So, HTML5 Notifications are an interesting little API, in that they’re not a formal specification by W3C - in fact, this API was first implemented by the Chromium project, and it seems to be a feature that will continue on the fringe of modern browsers only (i.e. - this probably isn’t coming to Internet Explorer).

They are quite powerful though - it’s a non-intrusive way of letting the user know something has happened, without reverting to an alert(), or having to load a Javascript library, which will still only work if the page is currently visible.

Adding the notifications though, it actually very simple - all the heavy lifting is done by the web browser - all that we need to do is:

1. Request permission to display notifications

2. Check that we have permission to display notifications

3. Set up the notification

4. Display the notitication

Permission needs to be requested, since you’ll be displaying notifications even if the user is not currently looking right at the page. We need to check that we have permission before we try and display anything to avoid errors, and then we can actually show the user the notification.

My Implementation

I was able to centralize the processing of Notifications in On the Spot by writing a Coffeescript class that handled the permissions (request & check), set up and display of notifications. This class is easy extensible later on if I need to add any new notifications as well. Here it is!

OnTheSpot.Notification = {

setup: ->

window.notifications = window.webkitNotifications unless window.notifications

if window.notifications && window.notifications.checkPermission() == 0

OnTheSpot.Notification.supported = true

else

OnTheSpot.Notification.supported = false

requestAccess: ->

window.notifications.requestPermission();

trackPlaying: (track) ->

return unless OnTheSpot.Notification.supported == true && track

window.notifications.createNotification(

'/assets/apple-touch-icon-precomposed.png',

track.name,

'On the Spot :: Track Playing'

).show()

}The flow of this class is:

- Add a document.ready event listener in jQuery, and call the

requestAccessfunction, when a button is clicked (you must request access from a button or link click, otherwise the browser will not actually ask the user for permission) - Call

setup- this function performs some checks to calculate whether we’re able to use and display notifications. - To show a notification, just call

trackPlayingwith the track data - the class will set up the notification and display it.

Downsides

The main downside to notifications is browser support. Unless your users are running on Safari 6+, Chrome for Android, or Chrome, notifications won’t work for you. Firefox docs indicate that some support for notifications may be in the pipeline, but more likely this support is going to be in Mozilla’s efforts to support ‘desktop’ web apps. Internet Explorer, Opera and other mobile browsers have no support at all, with none planned.

The other downside to the notifications is that they are (unsuprisingly, but still), only going to work when the page generating the notifications is open in a tab somewhere. Page focus isn’t necessary, but the generating page must be open. There might be a way to get around this by using Web workers, but I’ve got no concrete proof that this works.

Upsides

The main upside to notifications is that they reflect the native theme of the OS, are expected and anticipated behaviour from the user, and are generally easy to do, without compromising on look or feel.

They are also easy to generate, and ‘float’ apart from the actual browser application. This means that you don’t need to have the browser visible on the screen to see notifications. They also work without the page being visible (which is required for all other notification techniques to work, which tend to style a div on the page to look and behave like a notification), and, on OS X, appear in the Notification Center, which is pretty neat - users can click on the notification to go back to the application.

Overall, notifications are pretty cool, albeit with the proviso that they’re not used for anything important. They do require user opt-in to work, but once this permission is granted, they are simple and easy to use.