Whakamāori te Latter

Introduction

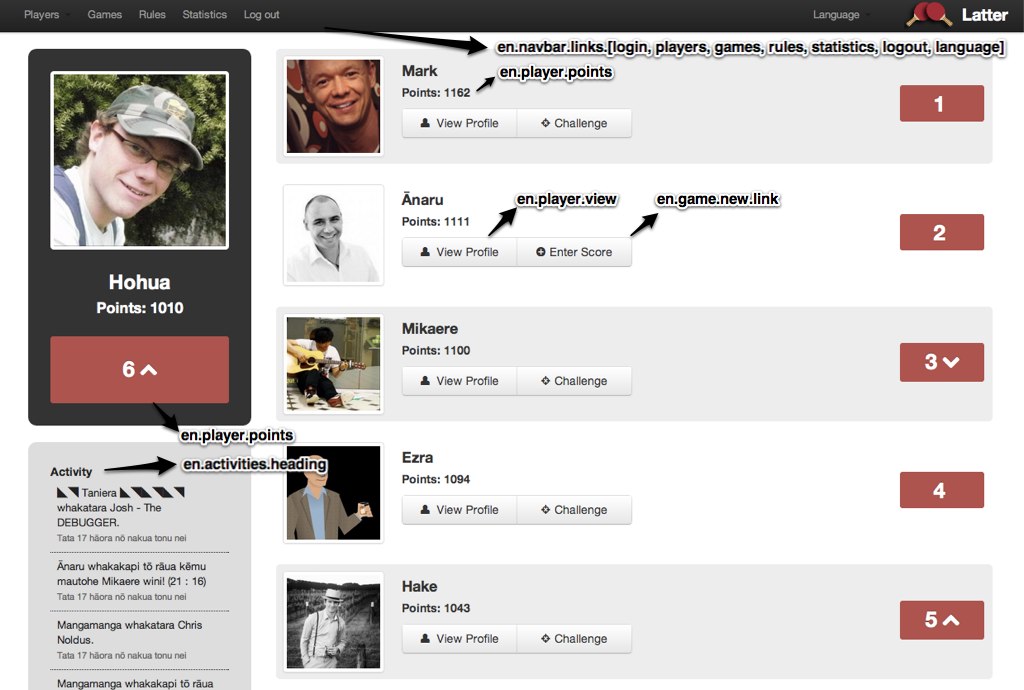

I’ve spent the last week translating Latter (really badly) into Māori using Rails’ I18n support. Since this is the first time I’ve done a full site translation, I wanted to detail how I did this here.

First, I’ll quickly explain how Rails I18n support works. Essentially, it’s a key-value store - you specify a ‘key’ which represents a bit of text like this:

I18n.t('player.create.success')The I18n module then takes this key, and looks up the ‘value’ that is stored in a YAML file, that, for this string, might contain a snippet like this:

player:

create:

success: 'Player was created successfully'It then substitutes the request for the string value for the current language, with the string value in the translation file (in this case, ‘Player was created successfully’)

The main advantage of I18n is centralization. Moving all the messages and small bits of text used all over the site makes it much easier to change content, try out different wording in certain areas, but most significantly, to offer support for multiple languages globally by changing just a couple of files.

Adding Te Reo Māori to Latter

The process of adding Te Reo to Latter was pretty simple - just time consuming. Initally, the bulk of the work was just finding translatable strings of text, and adding English translations for them, so that I could later add support for Māori. This process goes much more smoothly when you know where to look:

- Flash messsages in the controller

- Links and buttons

- Model-based forms

- Navigation and Layout

The next challenging bit that I didn’t realize would be difficult is the organization of keys into a logical structure where particular strings are going to be easy to find and maintain. The strategy that I chose to stick with is the following:

- Resource - the name of the resource, for example, Player, Game, Score. I preferred singular forms of names, as these more closely relate to the source class or model

- Action/Category - the controller action to which the translation belongs, or, if the string is for a specific area of the layout or a page, then an identifier for this idea

- Identifier - a key that identifies the string uniquely.

For example:

# Resource

player:

# Action

update:

# Key

success: 'Player updated successfully'By this point, I had the bulk of the application translated into English - that is, rather than having key messages, labels and actions specified in the HTML markup, I had moved it into config/locales/en.yml - the file that Rails loads when the application starts, and where it looks for translations.

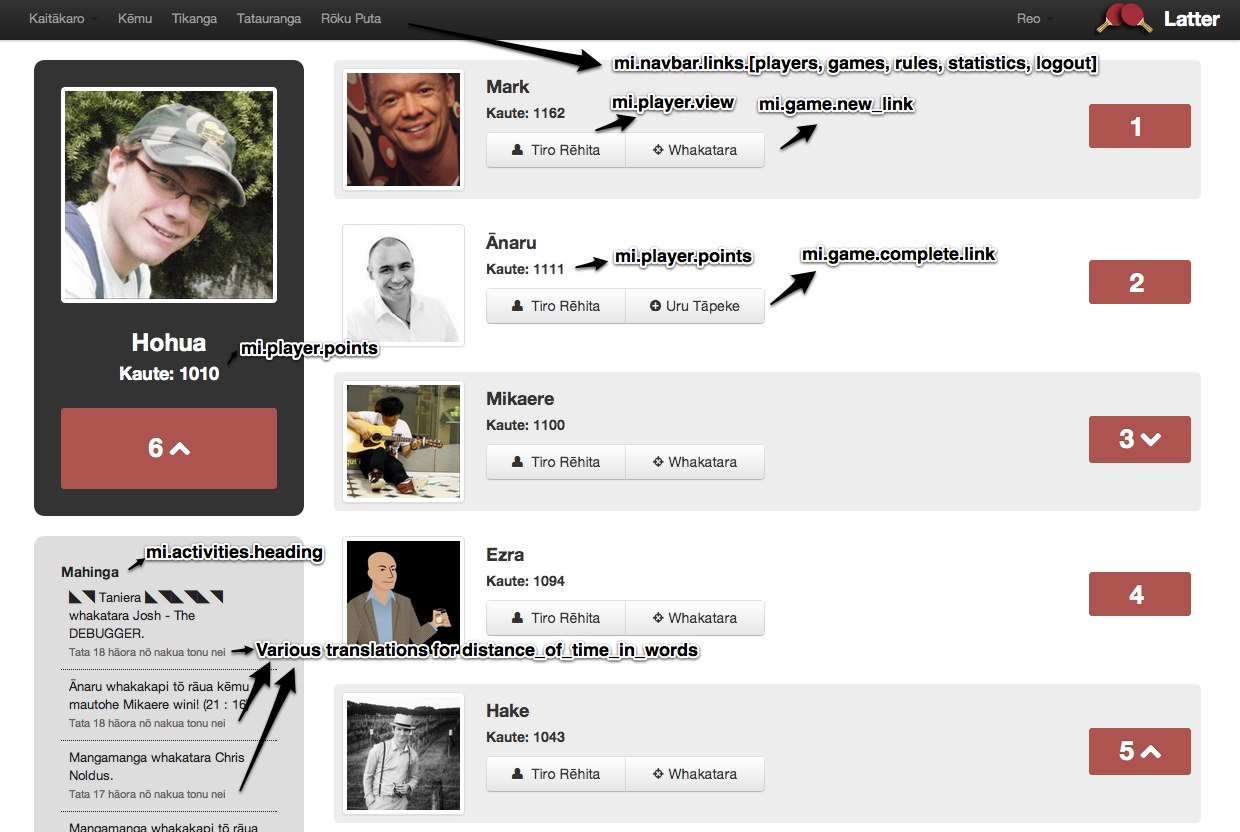

The next step, then is to add another language. This process in itself is actually very simple. Simply copy the en.yml file to mi.yml, and begin translating!

cp config/locales/en.yml config/locales/mi.ymlI found Māori quite a hard language to translate, for a few reasons. I had no prior experience with translating content, and a fairly weak grasp on Māori language constructs and syntax. Because of this, I wouldn’t be at all surprised to discover a range of minor errors in the translations, however I did find that having a central file to refer back to, as well as a fairly standard and simple vocabulary made this process much more simple.

The translation process itself is very simple. Given a translation within config/locales/en.yml like the following:

en:

game:

index:

heading: All Gamesthen the Māori equaivalent in config/locales/mi.yml would look like the following:

mi:

game:

index:

heading: Katoa Kēmu– the keys for the translation never change, just the content, typically with one file being added for each new language.

Latter is the first Rails app that I’ve added full support for translations to. Māori was a really important language for me to add, as I feel that it’s a key part of the New Zealand identity and culture. Conveniently, it also tied in with Māori Language Week.

Overall, the translation project took about a week’s worth of evenings and parts of the weekend - maybe about 15 hours all told, but now that the initial setup work is complete, adding additional languages is simply a matter of translating the strings already present. This process could have been sped up further, had Rails had build-in support for Māori - while the rails-i18n project has translations for many languages, the absence of Māori meant that I had to provide my own translations for some areas. This is an area where I see a key opportunity to add I18n translations for Māori to Rails, however I don’t feel that my Māori language skills are adequate enough to provide a quality contribution.

Internationalization is an often overlooked part of most web sites and applications, especially in New Zealand, where Te Reo Māori is one of our three official languages. It’s worth noting that only a fraction of the non-government websites and applications I have seen that are intended for a New Zealand audience offer Māori as an alternative language, which is really something I’d like to see in the future.

I hope that this post has explained the translation process clearly, and perhaps may even help drive more internationalization efforts with Rails in the future.

-

Rails I18n

Locales and source code for the Internationalization support built into Ruby on Rails